Please Be Advised: This article contains descriptions of the conditions and treatment of Victorian mental health patients that some may find distressing.

Now and then I like to do some hard research on my family tree. As more new digitised documents are becoming more available online, I occasionally like to take a look to what new information I can find. The inevitability of such research leads to discovering stories of all sorts — even of heartache and sadness. One such story came to light recently in my own family tree.

A Strange Coincidence?

I was searching for a death for one of my 4x great grandmothers. It was one of those times when an ancestor seems to fall through the proverbial time-line and escapes into anonymity. But like a dog that refuses to give up its favourite toy, I don’t give up so easily. So after lots of research I found only one possible solution, even though it seemed unlikely.

Most of my family tree come from the county of Hampshire. As working class people of their time, they didn’t move around much; any moving was rarely that far away. So when I found a death in London, it really didn’t have the ring of ‘Eureka’. But as it was my only lead, I decided to take a closer look.

My 4x great grandmother was called Elizabeth Instrell. The surname itself is not a common one, and to find her name, and pretty much the same age, in a burial record was interesting, but I wasn’t expecting it to go anywhere — just to be a strange coincidence. The parish burial said that her abode had been a place called Camberwell House. I was intrigued and wanted to find out about it. I was astonished to find out that it was a lunatic asylum. Could this really be her?

The Research

More research led me to the Wellcome Library, which has an archive of documents from Camberwell House. Lots of these have been digitised and are available to view on their website.

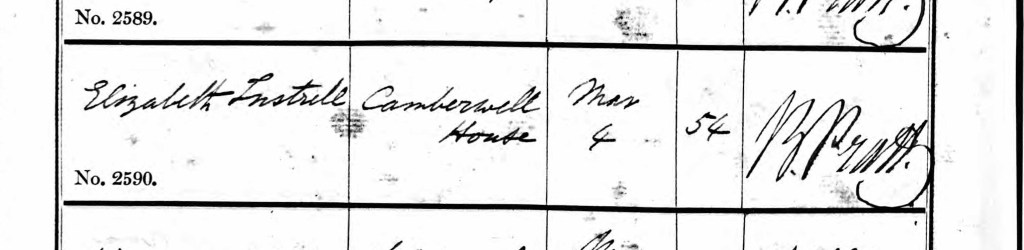

The first place I looked was a book of case reports. As it was in chronological order (as opposed to alphabetical), it took over 300 pages to find her. The document didn’t have any detail to give me a positive link to my Elizabeth, but her age at least matched.

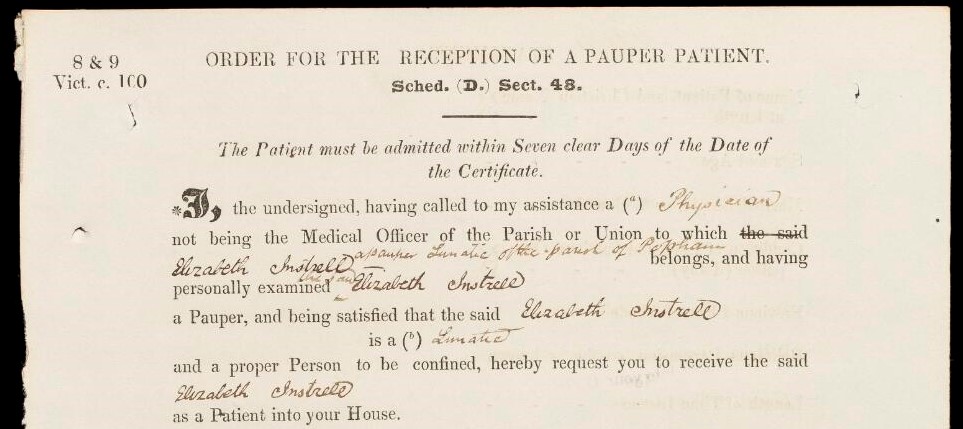

Then I found a book called ‘Reception of Pauper Patients.’ These are the referral documents for new patients of a poorer background. This book held the document that I needed. There I found the small link that matched — Elizabeth Instrell was from Popham — that’s my Elizabeth. Popham is a village, and the odds of it being someone else is pretty small. But why was she referred to an asylum in the first place, and why send her all the way to London?

The Asylum

Let’s start with that last question. Elizabeth arrived at Camberwell House in November 14th 1846. Her reception notes say that she had already been ‘insane’ for a year, and that her previous abode had been Lainston Lunatic Asylum, so it seems she had already been in an asylum for that time.

Lainston Lunatic Asylum is now called Lainston House and is a five star hotel, but their website mentions nothing about it’s past as an Asylum. The building sits NW of Winchester. Not much is known about Lainston House at this time, but I’ve managed to find something of it’s history.

There is a website which is an index to English and Welsh lunatic asylums and mental hospitals. It contains some information about Lainston Asylum. It was leased to a Dr Twynam between 1825–1847. Along with many other mental institutions, in 1844 it was subject to a report into the running of these asylums and the treatment of it’s patients called ‘The Report of the Metropolitan Commissioners in Lunacy‘. Lainston did not come out well. Dr Twynam was unresponsive to the changes that were recommended. Amongst the observations of the Commissioners who visited,

they noted that stables and outhouses were used as accommodation for the pauper patients.

Also they noted on one visit that seven women were found in hand-locks, chains and straight waistcoats, and the same seven and three others were chained to their beds at night. When the Commissioners complained, Dr Twynam said that the chains and hand-locks were “essential for safety.”

In October 1846, Dr Twynam had decided to quit the asylum. By 1847 it had closed. It maybe for this reason that Elizabeth was removed to Camberwell House. It had opened in 1846, so was perhaps in a position to take patients. There is no information about Elizabeth’s time at Lainston, so I have no idea if she was subject to chains or straight waistcoats; but as a pauper, I’m sure she would have been living in one of those outhouses or stables.

So, Why Was Elizabeth Sent to an Asylum?

This might sound like a easy question, but the Victorian understanding of mental health could be written on the back of a postage stamp. Many disabilities and health problems were lumped together as some sort of weakness of the mental faculties. It was not understood that many symptoms could be the manifestation of a physical illness. So, many that were sent to asylums were put under a psychological analysis, rather than looking at a physical cause and effect.

That seems to be the case for Elizabeth. From her case notes it mentions that Camberwell House had no information about her time at Lainston other than she was kept in confinement. At Camberwell, there are only three entries over her 15½ month stay. Even so they mention her continued physical and mental decline.

Elizabeth’s final days were in the asylum, dying on March 1st 1848. She is buried in London. It is highly likely that her family were not able to be there for her last day and funeral, as they would not be able to afford the cost. It makes me wonder how they coped with the decision to send her away, only for them to never see her again. It must have been heart-breaking.

This article was published in the March 2022 HGS journal. It has also been guest-posted on A Few Forgotten Women, a website about marginalised women (January 2023).

This blog post is not sponsored and the none of the links are affiliated.

Copyright © 2024 Charlotte Clark